Late‐life depression associated with Alzheimer’s disease

Yulin Chu, D.N.P., P.M.H.N.P.‐B.C., R.N.

Gaps: A concurrence of depression and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is evidenced, but their association is incompletely understood and probably complex. Late life depression (LLD) in AD is currently under-detected and undertreated.

Problems: Patients with LLD are much more likely to develop AD and have more disability and mortality. The elderly veterans are vulnerable to develop these two illnesses. On the other hand, the complex of their relationship made the assessment and treatment becomes challenging.

Outcomes: Effectively assessing and treating LLD will not only treat patients’ depressed mood, but also help slow down AD progression, maximize the function of patients, and reduce their disability, mortality, and huge cost.

Purpose: Increase nurses’ awareness to advocate for nonpharmacology treatment of LLD, improve nurses’ knowledge and assessment skills to successfully detect and treat LLD in AD.

Objectives

The participant will be able to:

- Identify the elderly veterans’ problems – LLD & associated AD.

- Understand the complex of the relationship between LLD & AD.

- The participant will be able to increase assessment skills to detect LLD.

- The participant will be able to demonstrate multi- approached treatment to LLD & AD.

AD – a common & very serious illness

- The 6th leading cause of death in US

- 5.5 million Americans currently suffer from AD, and will be increased to 7.1 million in 2025, and 13.8 million in 2050.

- On average, in every 4 seconds, there was a newly diagnosed AD in the US. One in 10 of the elderly people 65+ has AD.

- AD is also the most expensive disease in the nation

– in 2016 costs totaled $236 billion; and global costs exceeded $600 billion; the average family care for a pt. with AD is $215,000 throughout the entire course of the disease.

Minority’s disparity in AD

- African Americans have 1.5 times more likely having AD, Hispanics has earlier 7 yrs. of onsite for AD.

- Socioeconomic factors are blamed for this disparity – lower income & education, rural living.

- Health conditions such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, stroke and diabetes mellitus are known risk factors for AD.

- Cultural factors.

LLD – the most common mental illness in elderly

- Depression is the most common mental illness in older adults. Nearly 7 million Americans aged 65+ suffer from LLD.

- Their severity of depression is also higher (additional 23% symptoms).

- Suicide rate of elderly Americans is higher.

- Other risk for medical problems, cognitive decline and dementia, and non-suicidal mortality

- LLD has its own special features and characteristics. It is difficult to be detected.

- The efficacy of pharmacologic treatment of LLD is limited. Up to 90% of people with LLD don’t receive adequate care.

- Antipsychotics reduce acetylcholine in the brain and further damage brain.

Veterans’ disparity in LLD

- Veterans are primarily old males with increased prevalence of Hispanic and African Americans.

- Below average in socioeconomics, above average in medical co-morbidities & functional disabilities.

- Above 1/10 older veterans is depressed, a rate is

> 2x than that found in the general population. - Elderly veterans may not recognize and report their depression; up to 2/3 of them stopped their medicines.

Alzheimer’s Dementia

- Dementia – Overall term that describes a wide range of symptoms

- AD (termed in 2017) Common form of dementia (60- 80%)

– affects memory, thinking and behavior

– Fatal, slowly progressive – Starts 5, 10 or even 20 years before symptoms appear.

– Top 10 cause of death that has no cure, no means of prevention, and no disease-modifying treatments.

AD Video: https://youtu.be/7_kO6c2NfmE

Causes of AD/dementia

There is no one test to determine if someone has AD/dementia.

- Age, family history, & APOE-e4 gene

- Depression

- Medication side effects

- Excess use of alcohol

- Thyroid problems

- Vitamin deficiencies

Biomarker based diagnosis

- Plaques are deposits of a protein fragment called amyloid-β that build up in the spaces between nerve cells.

- Tangles are twisted fibers of another protein called tau that build up inside cells.

- Plaques and tangles tend to spread through the cortex as AD’s progresses – the dominant model in past 25 yrs.

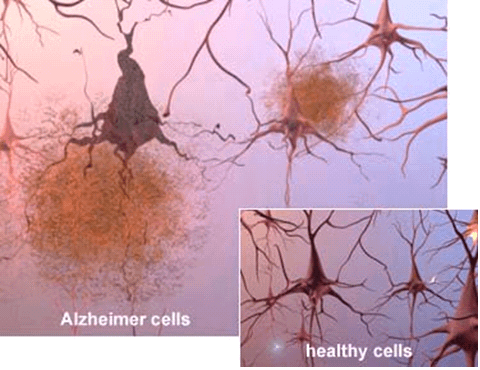

AD – plaques & tangles

Scientists can also see the terrible effects of Alzheimer’s disease when they look at brain tissue under the microscope:

Scientists can also see the terrible effects of Alzheimer’s disease when they look at brain tissue under the microscope:

- Alzheimer’s tissue has many fewer nerve cells and synapses than a healthy brain.

- Plaques, abnormal clusters of protein fragments, build up between nerve cells.

- Dead and dying nerve cells contain tangles, which are made up of twisted strands of another protein.

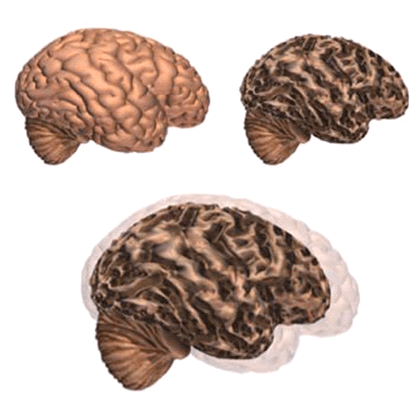

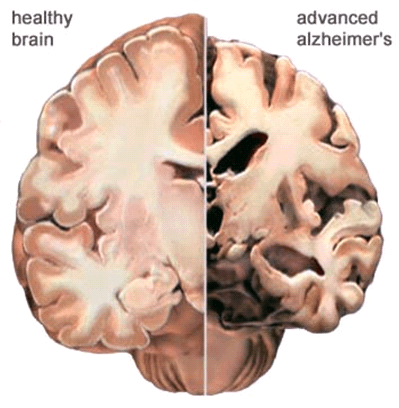

AD – brain changes

Alzheimer’s disease leads to nerve cell death and tissue loss throughout the brain. Over time, the brain shrinks dramatically, affecting nearly all its functions.

These images show:

- A brain without the disease

- A brain with advanced Alzheimer’s

- How the two brains compare

In the Alzheimer’s brain:

- The cortex shrivels up, damaging areas involved in thinking, planning and remembering.

- Shrinkage is especially severe in the hippocampus, an area of the cortex that plays a key role in formation of new memories.

- Ventricles (fluid-filled spaces within the brain) grow larger.

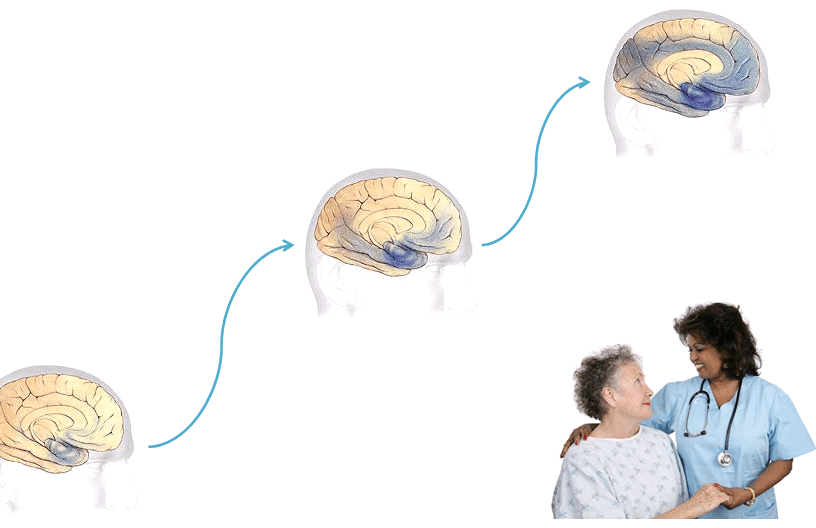

Progression through the brain

- Earliest Alzheimer’s – changes may begin 20 years or more before diagnosis.

- Mild to moderate Alzheimer’s stages – generally last from 2 – 10 years.

- Severe Alzheimer’s – may last from 1 – 5 years.

The rate of progression varies greatly.

Progression of MCI ‐‐> AD

- Diagnosis of MCI – some cognitive impairment but not meet AD criteria = MCI. About 56% of MCI were developed to AD

- AD diagnosis: 1. Biomarker based diagnosis; 2. The severity of cognitive or functional impairment (either using DSM or NINCDS-ADRDA criteria).

- LLD would increase the risk of this process. Some experts believe that depression is often one of the first symptoms of AD.

AD Dx in DSM‐V

Symptoms vary greatly – Significant impairment of 2 core mental functions below:

- Memory

- Communication and language

- Ability to focus and pay attention

- Reasoning and judgment

- Visual perception

Depression

- A mental disorder characterized by episodes of all- encompassing low mood accompanied by:

- low self-esteem

- loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities.

Depression – common symptoms

| Difficulty concentrating and remembering | Loss of interest in activities or hobbies |

| Fatigue and decreased energy | Overeating or appetite loss |

| Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, helplessness | Persistent aches or pains |

| Insomnia, or excessive sleeping | Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” feelings |

| Irritability, restlessness | Thoughts of suicide |

Depression in patients with AD

LLD: Late-onset of major depression; in 65 & older associated with AD (dementia). Special features:

- Irritability

- Anxiety

- Sun Down Syndrome (different than insomnia)

- Worrying

- Agitation or psycho motor agitation (PMA)

- Apathy – not necessarily sadness or anhedonia, but numbness of emotion

The case study 1

- “I have no purpose coming to this world.” Mr. A. is an 80 years old African American veteran carrying a diagnosis of Probable AD. Pt. and his wife reported that he has developed depression with suicidal ideation (SI) after being consistently thinking about where he is from, where he has been, and where he is going to. Patient was a chemist and had his own successful business company. After his retirement, especially after showing AD symptoms, he developed hopeless and worthless idea with depression and intermittent SI.

- Over the course of AD development, his symptoms were changed: Early stage: short memory loss, repeated questions, sadness, anhedonia, insomnia, social isolation, etc.; Late stage now: confusion, Sun down Syndrome, apathy, anxiety and agitation, etc.

Relationship of LLD & AD

- The prevalence of depression disorder among the elderly with AD – about 20-40%.

- There is a correlation between these 2 diagnoses. LLD is a unique depression subtype as concurrent disease of AD.

- There are hypotheses of the etiologies of their correlation.

- The symptoms of the depression change over the course of AD development.

Etiology hypothesis of their association

- Serotonin (5-HT) neuron and neurotransmitter loss in normal aging and neuropsychiatric diseases of late life may contribute to LLD; a combination of disturbances in cholinergic and serotonergic function may play a role in cognitive impairment in AD

- Gene encoding the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has been demonstrated as a candidate for AD-related depression susceptibility

- Research about plasma amyloid beta peptides (Aβ42 related to depression) leads a high ratio of Aβ42, a biomarker of AD may represent a unique depression subtype (absence of ApoE4)

- PET scan shows depression is associated with greater atrophy in AD @ affected regions: frontal, parietal, & temporal white matter atrophy

Symptoms change

- Overlapped symptoms of LLD & AD: apathy, loss of interest, impaired ability to think & concentrate, psychomotor changes, dysphoria, irritability, sleep disturbance, & social withdrawal.

- LLD patients may lack of insight, and poor recollection of symptoms, may be less likely to talk about or attempt suicide. SI may not last long, but comes and goes.

- As AD progressing, LLD symptoms: Dysphoria or feeling of sadness, irritability and apathy, finally anxiety, agitation, or aggression.

- NIMH established a guideline for diagnosing LLD: reduces emphasis on verbal expression, and includes irritability, and social isolation.

AD assessment

Evaluation tools for AD:

- Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE)

- Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR)

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

- Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ)

Assessments:

- Neuro-psychotests

- Expert consults

- Medical/medication/family history

- Physical and neurological exam

- Lab studies & imaging – CT, MRI, PET scan of the brain

LLD assessment

- Evaluation tool – Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)

- Self–report of depression symptoms was assessed in the population interview at beginning and annual intervals measured by GDS

- GDS scoring 0-15. ≥ 5 → “depressed”

- GDS <5 → “non-depressed”

Assessment of their relationship

- Impact of depression to cognition decline is measured and analyzed to compare cognitive scores between depressed elderly participants and non-depressed subjects

- Comparison is divided into different groups according to their age, gender, races, history of depression, and history of physical conditions, especially history of stroke

- Most studies results: there was a correlation between these 2 illnesses.

The case study 2

- Mr. B. is a 92 year old Caucasian Male, widower, lives alone. He has past psychiatric history of probable AD and MDD, recurrent, moderate, but denies any symptoms of current “depression or anxiety,” denies SI or SA.

- Performed GDS = 13/15 = severe depression. ? E.g., dropped many activities, feel his life is empty, not happy, helpless, life is worthless, lack of energy, memory loss, not interested to be alive. Only + answer – not afraid of bad thing is going to happen to him. Apathy?

- How about in early stage of AD? Or in late stage of AD?

Current pharmacologic Tx for AD

- Mainly uses 4 FDA approved

- acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Aricept, Exelon, Razadyne.

- glutamate pathway modifier: Namenda

- Biopsy/PET scan results not directed matching amyloid with AD; antiamyloid drugs (prevent/remove amyloid) didn’t slow the onset of AD. Amyloid deposits are a trigger for other pathologies in the brain & become irrelevant once those mechanisms come into play?

- In 11/2016, Eli Lilly abandoned their attempts to test the drug Solanezumab (anti-amyloid drugs), said “it had failed to halt even early stages of AD.”

- The problem: drug didn’t do what it was supposed to do; the underlying cause for AD most scientists work from is complete baloney building the studies on sand rather than stone.

- Shaping the search from amyloid hypothesis to disease-modifying treatments for AD.

Nonpharmacological Tx for AD

Cognitive stimulation, reality orientation therapy, Validation therapy, Behavioral therapy:

- Education about the disease, symptoms, and progress, modifying disease risk factors

- Assigning homework for physical and brain exercise, diet, and adjust medicines

- Encouraging social activity engagement

- Introducing information access, support network, and AD research programs

LLD Tx

Pharmacotherapy (mainly SSRIs); psychotherapy; follow- up monitoring

- Most of experts believe that LLD is treatable. However, the treatment of depression in AD may be very challenging, because it is connected with AD treatment.

- SE of antidepressants – falls, rashes, reduced oral intake, weight loss, constipation, increased confusion, or delirium, bradycardia, hyponatremia

- Wide use of antipsychotics among the elderly not only impaired their cognition but also significantly increases the mortality

Multi‐approached Tx for LLD

Multi-approach treatment would demonstrate better outcomes:

- Psychotherapy/non-pharmacological supportive therapies.

- Physical and cognitive activities.

- Enhance social engagement.

- Diet

- Ethical modifications for minorities and patients with physical/mental disabilities.

Follow‐up the case study 1

- Mr. A has been on the combination of Aricept, Namenda for AD; on citalopram for LLD, but developed bradycardia, why?

- Switched citalopram to Paroxetine that induced adverse anticholinergic effects – dry mouth, blurred vision, tremor, spontaneous defecation, and passive avoidance, and in some cases, dementia-like symptoms.

- Switched to sertraline (on Aricept), Mr. A had stomach cramping, nausea and vomiting in the 1st week of switching.

- Switch to fluoxetine (minor SE, but efficacy)? Other antidepressants? Mr. A ended up with no antidepressant.

The case study 3

- Mr. C. is an 84 year old male with a past psychiatric history of AD (about 10 yrs.), generalized anxiety disorder, and insomnia, and past medical history of osteoarthritis, varicose veins, gout, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia.

- Medications: for cognition – memantine 5 mg QAM + 10 mg QHS; donepezil 10 mg QHS + 5 mg daily; for anxiety: hydroxyzine 25 mg bid; For sleep: mirtazapine 7.5 mg QHS.

- He has a very supportive family: wife and daughter came with him for every visit; they are very care about him; the pt. has no LLD symptoms.

- Multi-approach treatment to Mr. C in last 5 yrs..: relatively stable mental status; the important value of the treatment – enhance social engagement – education about the disease progress, support therapy, homework, monitor & F/U.

- Results: MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) = 20/30 (2013), ->17 (2014), -> 19 (2015), ->17 (2016).

GDS (Geriatric Depression Scale) = 4/15 (2015), -> 2/15 (2016). No LLD, and cognition has been not declined sharply. At least, he is happy, no Sxs of severe anxiety or agitation

References

Alzheimer’s Association. 2017. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement 2017; 13:325- 373.

Barnes, D. E., Yaffe, K., Byers, A. L., McCormick, M., Schaefer, C., Whitmer, R. A. (2012). Midlife vs. Late-Life Depressive Symptoms and Risk of Dementia – Differential Effects for Alzheimer Disease and Vascular Dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 69(5):493-498

Becker, J. T., Chang, Y. F., Lopez, O. L., Dew, M. A., Sweet, R. A., Barnes, D., Yaffe, K., Young, J., Kuller, L., Reynolds, C. F. (2009). Depressed mood is not a risk factor for incident dementia in a community- based cohort. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(8):653-63

Bierman, E. J., Comijs, H. C., Jonker, C., Scheltens, P., Beekman, A. T. (2009). The effect of anxiety and depression on decline of memory function in Alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics. 21(6):1142-7.

Blazer, D. G. (2003). Depression in late life: Review and commentary. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 58A (3), 249- 265

Borroni, B., Grassi, M., Archetti, S., Costanzi, C., Bianchi, M., Caimi, L., Caltagirone, C., Di Luca, M., Padovani, A. (2009). BDNF genetic variations increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease-related depression. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 18(4):867-75.

Contador-Castillo, I., Fernández-Calvo, B., Cacho-Gutiérrez, L. J., Ramos-Campos, F., Hernández-Martín, L. (2009). Depression in Alzheimer type-dementia: is there any effect on memory performance]. Revue Neurologique, 16-30; 49(10):505-10. Spanish.

Dillon, C., Machnicki, G., Serrano, C. M., Rojas, G., Vazquez, G., Allegri, R. F. (2011). Clinical manifestations of geriatric depression in a memory clinic: toward a proposed subtyping of geriatric depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 134(1-3):177-87.

Evans, J. (5/1/2011). Caring for the ages. AMDA. Retrieved from http://www.caringfortheages.com/issues/may-2011/single-vview/the-ethics-of-antipsychotics-in- alzheimer/ba6ff721b07f61a5d15888345dd9e1bc.html

Hattori, H. (2009). Elderly depression and depressive state with Alzheimer’s disease. Nihon Rinsho, 67(4): 835-44. Japanese.

Isingrini, E., Desmidt, T., Belzung, C., Camus, V. (2009). Endothelial dysfunction: A potential therapeutic target for geriatric depression and brain amyloid deposition in Alzheimer’s disease? Current Opinion In Investigational Drugs, 10(1):46-55.

Kerr, M. (2012). Learn about how depression affects the elderly, including symptoms, statistics, treatments, and more. Healthline. Retrieved from http://www.healthline.com/health/depression/elderly-and-aging

Lee, J., et al., & the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2012). Depressive symptoms in mild cognitive impairment predict greater atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease-related regions. Biological Psychiatry, 71(9):814-21.

Lyketsos, C. G.; Johns Hopkins medicine. (2012). Treating Depression in Alzheimer’s Patients. Memory Disorders Review, Summer Issue; page: 22-32.

Meltzer, C, et al, (1998). Serotonin in Aging, Late-Life Depression, and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Emerging Role of Functional Imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology, 18, 407–430

Mortby, M. E., Maercker, A., Forstmeier, S. (2011). Midlife motivational abilities predict apathy and depression in Alzheimer disease: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 24(3):151-60

Nandipati, S., Luo, X., Schimming, C., Grossman, H. T., Sano, M. (2012). Cognition in Non-Demented Diabetic Older Adults. Current Aging Science, 5, 131-135.

NIH CDC. (1994). Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.

Porta-Etessam, J., Tobaruela-González, J. L., Rabes-Berendes, C. (2011). Depression in patients with moderate Alzheimer disease: a prospective observational cohort study. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 25(4):317-25.

Saczynski, J. S., Beiser, A., Seshadri, S., Auerbach, S., Wolf, P. A., Au, R. (2010). Depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: the Framingham Heart Study. Neurology, 75(1):35-41.

Span, P. (2013). Suicide rates are high among the elderly. New York Times, 8/7/2013

Starkstein, S. E., Dragovic, M., Jorge, R., Brockman, S., Robinson, R. G. (2011). Diagnostic Criteria for Depression in Alzheimer Disease: A Study of Symptom Patterns Using Latent Class Analysis. Geriatric Psychiatry, 19:551–558)

Sun, X., Chiu, C. C., Liebson, E., Crivello, N.A., Wang, L., Claunch, J., Folstein, M., Rosenberg, I., Mwamburi, D. M., Peter, I., Qiu, W. Q. (2009). Depression and plasma amyloid beta peptides in the elderly with and without the apolipoprotein E4 allele. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 23(3):238-44

Tsopelas, C., Stewart, R., Savva, G. M., Brayne, C., Ince, P., Thomas, A., Matthews, F. E.; Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. (2011). Neuropathological correlates of late-life depression in older people. British Journal of Psychiatry, 198(2):109-14

UsAgaistAlzheimer’snetwork, 2017. Retrieved from: http://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/crisis?gclid=Cj0KEQjwrsDIBRDX3JCunOrr_YYBEiQAifH1FjCl6w3C 2LbHF_eiJcpn1NFUVBZGeBwhlQO-cSsuF_8aAtC28P8HAQ

United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). (2011). One in ten veterans is depressed. Retrieved from http://www.va.gov/health/NewsFeatures/20110624a.asp

VA. (2014). Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2014-2020 strategic plan. Retrieved from http://www.va.gov/op3/docs/StrategicPlanning/VA2014-2020strategicPlan.PDF

Wadsworth, L. P., Lorius, N., Donovan, N. J., Locascio, J. J., Rentz, D. M., Johnson, K. A., Sperling, R. A., Marshall, G. A. (2012). Pharmacotherapy treatment of depression in patients with neurodegenerative diseases: where are we? Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 34(2):96-111.

Wang, L., Potter, G. G., Krishnan, R. K., Dolcos, F., Smith, G. S., Steffens, D. C. (2012). Neural correlates associated with cognitive decline in late-life depression. Geriatric Psychiatry, 20:653–663.

Weintraub, D., Rosenberg, P. B., Drye, L. T., Martin, B. K., Frangakis, C., Mintzer, J. E., Porsteinsson, A. P., Schneider, L. S., Rabins, P. V., Munro, C. A., Meinert, C. L., Lyketsos, C. G.; DIADS-2 Research Group. (2010). Sertraline for the treatment of depression in Alzheimer disease: week-24 outcomes. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(4): 332–340.

Wilson, R. S., Hoganson, G. M., Rajan, K. B., Barnes, L. L., Mendes de Leon, C. F., Evans, D. A. (2010).

Temporal course of depressive symptoms during the development of Alzheimer disease. Neurology, 75(1), 21-26.