TMS: An effective treatment for depression

Gagandeep Kaur, M.D., Rif S. El-Mallakh, M.D., Ahmad S. Bashir, M.D., Paul Kensicki, M.D., Steven Lippmann, M.D.

Abstract. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a promising therapeutic option in psychiatry, especially for patients with treatment resistant affective illnesses. Some depressed people who are refractory to conventional therapies improve with TMS. Complications or side effects are uncommon. Administration requires no anesthesia, so patients can be fully alert and decisional during and after each session. TMS can be an acute therapy and also be a long-term intervention.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a relatively newer treatment option in psychiatry. Three decades ago, it emerged as a research technique to study cerebral mapping (1). Overtime, investigational interest focused on applications in neurological and psychiatric illnesses (2). In 2008, the American Federal Drug Administration approved it for treating depression (3), and since 2010, the University of Louisville Department of Psychiatry started utilizing it for the management of refractory depression cases and/or chronic pain. Over three years of administering this therapy in a small population of patients, its efficacy in many cases appears to be clinically sound. There were few side effects noted.

Physics

Faraday’s Law is the origin of TMS development (4). Faraday’s law states that changing magnetic fields focused near conductors produce an electric current. Pulsed magnetic fields induce electric currents which are well conducted in the cerebral cortex resulting in depolarization of brain neurons.

Physiology

The left prefrontal cortex (PFC) is associated with controlling mood (5) and has diminished activity in patients with affective disorders (6,7). When TMS is administered to the left PFC, there is increased blood flow in this region, as documented in functional magnetic resonance imaging (8) also, there is increased dopamine release by basal ganglia, evident on positive emission tomography studies (9). These physiological changes improve mood, outlook, and behavior (5-9).

Indications

TMS is utilized for depressed patients who have not responded during a current depressive episode to at least one antidepressant drug which was administered at the recommended effective dosing and time frame (3). There is also ongoing research and clinical use of TMS in treatment of patients with cerebrovascular infarcts, tinnitus, auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia, seizures, Parkinson’s disease, chronic pain, dystonias, pregnancy, and pervasive developmental disorders, etc. (10-17).

Method of Administration

Patients are first prescreened for history of seizures, aneurysm, brain mass or cancer, implanted metallic objects, and pacemakers. They are then seated in a comfortable reclined posture, adjusted for comfort, and settings saved on the computer. The TMS provider first locates the left primary motor cortex by magnetic stimulation over the scalp to create a motor reflex of the right thumb, observed by a muscular twitch (18). Then, the threshold for stimulation is determined and the TMS coil is positioned 5.5 centimeters anterior to the left primary motor cortex, which is on the scalp at proximity to the left PFC. At this location, the treatment is started. TMS is generally administered five days a week for four to six weeks (18). Antidepressant pharmacotherapies are usually maintained during and after the TMS.

Thirty treatment sessions characterize a typical course. Once the person is significantly improved, the therapy frequency slows to twice per week, and then to weekly therapy, if remission is sustained. Clinical follow up is recommended. Discontinuing TMS is a decision individualized by the treating physician and the patient depending on the clinical status. Periodic maintenance TMS can be selected for people who have responded, but who once again relapsed with affective complaints or it may be utilized to sustain remission.

Contraindications

TMS treatment is not recommended for individuals with poorly controlled epilepsy. Thus, it is important to prescreen for the likelihood and status of ictal disorders; however, TMS may be an appropriate option in well controlled seizure patients (18). It is not utilized in people with implanted electronic devices, like defibrillators, vagal nerve stimulators, or pacemakers, etc. Similarly, TMS also may not be offered to those with conductive ferromagnetic objects like coils, staples, aneurysm clips, bullets, or electrodes in their body (3,18); however, TMS has been utilized at our clinic without any adverse events in the treatment of chronic pain in a person with an implanted titanium wire. TMS safety during pregnancy has yet not been well clarified, but research is ongoing. Similarly, TMS treatment in adolescent cases is not well established because of the risk of inducing seizures. Recent TMS research conducted on seven teenagers over eight weeks documented that five of seven subjects responded well, without any adverse effects (19).

Double-blind, Randomized Controlled Research

In 2006, research including 50 subjects with half receiving left and also right prefrontal cortex TMS and half getting sham applications, revealed significant efficacy in those with treatment-resistant depression (20). Good responses were also reported during 2007 in a similar study of 301 medication-free patients divided between left-sided TMS and sham therapy over 4-6 weeks, at a motor threshold of 120% and at 3,000 pulses/session (21).

Contrary results the same year were noted in 127 antidepressant medicated subjects at a motor threshold of 110% at 2,000 pulses/session (22). Poor efficacy was echoed the following year in 59 cases that were treated for two weeks at a motor threshold of 110% and 1,000 pulses/session (23).

A 2009 study done on 301 patients with major depression that were given TMS at a motor threshold of 120% at 3,000 pulses/session was conducted in different countries and supported the efficacy of TMS as a single therapy (24). An investigation with 199 drug-free subjects who were administered TMS in 2010 at a motor threshold of 120% at 3,000 pulses/session, documented that TMS as a monotherapy has better outcomes than sham exposures (25).

Research in 2011, studied 19 subjects which included 14 diagnosed as unipolar depression without psychotic features, one experienced major depression with psychotic features, and there were two bipolar I and bipolar II cases, each. TMS was administered with a motor threshold of 120% at 3,000 pulses/session. From this group, 37% achieved full remission and 16% reported clinically significant improvement (26).

Problems

Headache and scalp discomfort are the most frequent post-TMS complaints (18). In those cases, patients are advised to take acetaminophen before coming to treatment. During a TMS session, facial or right arm muscular twitching often occurs, which can be corrected by changing the position of the coil. Less common is transient pain in the ocular and/or dental regions. TMS can precipitate a convulsion, yet that is a rare event (3). The TMS apparatus is noisy, but no ill affect on hearing has been reported; ear plugs utilized during the treatment decrease the sound considerably (18). During our treatment sessions, one patient reported insomnia with anxiety, another experienced sleepiness, and one had vivid dreams. One person complained of a brief difficulty at walking shortly after each treatment session.

Advantages

TMS requires no anesthesia, thus patients remain fully awake. They are thus at their baseline decisional capacity for medical discussions or consent procedures. Cognition, memory, and dexterity are not impaired (19). Following each session, one is able to perform intellectual and motor tasks without compromise; it does not prohibit driving or ability to operate machinery.

Disadvantages

TMS is very expensive. Sustained improvement in mood is often observed, but that experience is not universal. Patients pay for it out of their own personal resources as it is not always reimbursed by health insurances in the United States. Certain third party payers currently do provide coverage on a case-by-case basis. At this time, the safety during pregnancy is yet to be established (4). The literature documents that TMS is not as powerful at inducing affective symptom remission as is electroconvulsive therapy (19,25,27); however, it still offers hope for people with difficult to treat depression cases. In the near future, TMS might become routinely covered by medical insurance and be more widely utilized.

Table 1.

| Age | Diagnosis | Duration | PHQ-9 before TMS | # of TMS | PHQ-9 after TMS | Result | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 | major depression | 4 years | 19 | 28 | 4 | Good | nausea, sleepiness |

| 55 | major depression | 17 years | 17 | 30 | 17 | Poor | none |

| 77 | atypical depression | 3 years | 2 | 30 | 2 | Poor | transient difficulty walking |

| 61 | major depression | 1year | 19 | 30 | 9 | Good | anxiety, insomnia |

| 66 | major depression | life-long | 19 | 30 | 11 | Fair | none |

| 60 | major depression | 35 years | 4 | 39 | 1 | Good | none |

| 44 | major depression | 23 years | 17 | 27 | 6 | Good | vivid dreams |

| 29 | major depression | 14 years | 26 | 30 | 18 | Poor | headache, reflex in arm |

| 65 | major depression | life-long | 15 | 43 | 2 | Good | reflex stimulation of frontalis muscle |

Our experience

By 2013, the University of Louisville School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry has treated nine patients with TMS, for a total of 287 sessions. Eight of them suffered major depression as an indication for treatment, and the ninth had atypical depression with chronic pain. They were administered between 27 and 43 TMS treatment sessions at 5,000 pulses/session at 120% motor threshold. Improvement was overt in five subjects, three reported some response, and one improved only slightly, without sustained progress. Out of the nine patients, two of them relapsed into depression within six months and later received electroconvulsive therapy because of not being able to afford TMS again, while ECT is covered by health insurance.

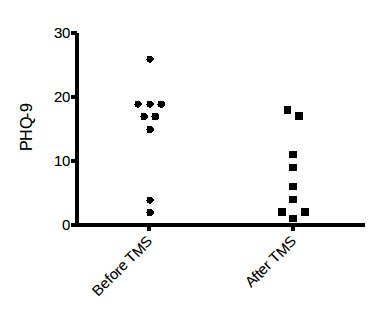

Figure: Change in PHQ-9 before and after TMS treatment in 9 subjects:

Conclusion

Severity was measured utilizing the 9-point Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a scale that was originally created to diagnose major depression (sensitivity and specificity of 0.88, each). It has been documented as reliable in measuring the severity of depression with 5, 10, 15, and 20, representing mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression (28). From the data accumulated in the figure, a graph is formed illustrating a paired t-test comparing the responses before and after treatment. It evidenced that the mean difference was 7.46 points (t = 4.154 and the 2-tailed P = 0.0032 is statistically significant). TMS was an effective therapy for patients resistant to past interventions. It was well tolerated.

Limitations

Our patient population was small (only nine subjects). The PHQ-9 score was the only standard test utilized to measure patient response.

References

1. Barker AT, Jalinous R, Freeston IL. Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of human motor cortex. Lancet. 1985; 325(8437): 1106-1107.

2. Dimyan MA, Cohen L. Contribution of transcranial magnetic stimulation to the understanding of mechanisms of functional recovery after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010; 24(2): 125-135.

3. Derstine T, Lanocha K, Wahlstrom C, et al. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Major Depressive Disorder A pragmatic approach to implement TMS in a Clinical practice. Ann Clin Psychiatr. 2010; 22(4 Suppl):S4-11.

4. Faraday M. Experimental researches in electricity, London, England. Richard & John Edward Taylor publishers;1849.

5. Davidson RJ. Well-being and affective style: neural substrates and biobehavioral correlates. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004; 359(1449): 1395-1411.

6. Drevets WC, Gadde KM, Krishnan KRR. Neuroimaging studies of mood disorders. In: Charney DS, Nestler EJ, Bunney BS, eds. Neurobiology of Mental Illness, New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999.

7. Speer AM, Kimbrell TA, Wassermann EM, et al. Opposite effects of high and low frequency rTMS on regional brain activity in depressed patients, Biol Psychiatry. 2000; 48(12):1133-1141.

8.Nahas Z, Lomarev M, Robert DR, et al. Unilateral left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation(TMS) produces intensity dependent bilateral effects as measured by interleaved BOLD fMRI. Biol Psychiatry. 2001; 50(9): 712-720.

9. Strafella AP, Paus T, Barrett J, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of human prefrontal cortex induces dopamine release in the caudate nucleus. J Neurosci. 2001; 21(15): RC157.

10. Kim YH, You SH, Myoung-Hwan K, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation-induced corticomotor excitability and associated motor skill acquisition in chronic stroke. Stroke. 2006; 37:1471-1476.

11. Kleinjung T, Eichhammer P, Langguth B et al. Long term effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in patients with chronic tinnitus. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2005; 132(4):566-569.

12.Hoffmann RE, Boutros NN, Hu S, Berman RM. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Lancet. 2000;355(9209):1073-1075.

13.Theodore WH, Hunter K, Chen R, et al. Trancranial magnetic stimulation for treatment of seizures: a controlled study. Neurology. 2002; 59(4): 560-562.

14. Elahi B, Elahi B, Chen R. Effect of transcranial magnetic stimulation on Parkinson motor function- Systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Movement Disord. 2009; 24:357-363.

15. Lefaucheur JP, Drouot X, Menard-Lefaucheur I, et al. Neurogenic pain relief by repetitive transcranial cortical stimulation depends on the origin and site of pain. J of Neurol Neurosur Psychiatr. 2004; 75(4): 612-616.

16. Nahas Z, Bohning DE, Molloy MA, et al. Safety and feasibility of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of anxious depression in pregnancy: a case report. J of Clin Psychiat. 1999; 60(1): 50-52.

17. Rodriguez-Martin JL, Barbanoj JM, Perez V. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2003; 2 (CD003387).

18. Neurostar University Self- Study Program, Neuronetics, Inc., Melvin, PA. 2009. www.neuronetics.com

19. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation provides a safe, effective alternative for adolescents with major depressive disorder. PsychUpdate Psychiatry and Psychology News From Mayo Clinic .2011;3(2).(MC7900-1111)

20. Slotema C, Blom J, Hoek H, et al. Should we expand the toolbox of psychiatric treatment methods to include repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)?A meta-analysis of the efficacy of rTMS in psychiatric disorders. J of Clin Psychiat. 2010; 71(7): 873-884.

21. Fitzgerald PB, Benitez J, de Castella A, et al. A randomized, control trial of sequential bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment- resistant depression. Am J of Psychiatry. 2006; 163(1):88-94.

22. O’ Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007; 62(11): 1208-1216.

23. Herwig U, Fallgatter AJ, Hoppner J, et al. Antidepressant effects of augmentative transcranial magnetic stimulation: randomized multicentre trial. Br J of Psychiatry. 2007; 191(5): 441-448.

24. Mogg A, Pluck G, Eranti SV, et al. A randomized controlled trial with 4- month follow-up of adjunctive repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left prefrontal cortex for depression. Psychol Med.2008; 38(3): 323-333.

25. Lisanby SH, Husain MM, Rosenquist PB, et al. Daily Left Prefrontal Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in the Acute Treatment of Major Depression: Clinical Predictors of Outcome in a Multisite, Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Neuropsychopharmacology.2009;34(2): 522-534.

26. Jr Schrodt G.R, Schrodt CJ, Schrodt ZA. A naturalistic study of office-based repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for treatment-resistant depression. J KY Med Assoc. 2011; 109(9): 271-276.

27. George MS, Lisanby SH, Avery D, et al. Daily left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy for major depression disorder. A Sham-controlled randomized trial. Arch of Gen Psychiatry. 2010; 67(5): 507-516.

28. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J of Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(9):606-613.

All authors are affiliated with University of Louisville School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Louisville, KY, USA. Correspondence Author: Steven Lippmann, M.D., 401 East Chestnut, Suite 610,

Louisville, KY 40202. Phone 502- 588-0674![]() 502- 588-0674 or 502-895-8330

502- 588-0674 or 502-895-8330![]() 502-895-8330. Email: s…@exchange.louisville.edu

502-895-8330. Email: s…@exchange.louisville.edu