Loss, trauma and suicide in war survivors

“I am constantly amazed by man’s inhumanity to man”

Primo Levi (1919-1987)

War can be defined as a state of usually open and declared armed hostile conflict between states or nations. About 30 armed conflicts are occurring now around the globe involving more than 25 countries (1). The majority of war-related violence is non-fatal and results in a variety of physical and mental health problems (2) (3) (4) (5) (6).

Although soldiers and civilians that endure war experiences face common and different stressors, their complex psychobiological response to trauma shares similarities. Additionally, socio-cultural conditions deeply influence individual and collective reactions to war. Resilience levels are also different from one group to another.

Acute anxiety disorders -such as acute stress reaction (ASR) and combat (or ongoing military) operational stress reaction (COSR) – or sub-acute and/or chronic anxiety disorders -such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and/or other non-otherwise specified anxiety reactions-, are potential consequences of war traumas. Prolonged grief disorder (PGD), complicated grief (CG), or major depressive disorder (MDD) are also probable sequelae of war experiences. These mood and anxiety categories are often comorbid and sometimes overlap with substance abuse disorders (7) (8). Suicidal behavior is also another possible consequence of war stressors linked with the above mention conditions.

Psychobiological responses to war experiences could be summarized and conceptualized as follows: a) depression, guilt, shame and/or ruminations on existential fears, as a reaction to symbolic and/or real “losses”; b) posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and other anxiety reactions, as a response to “life-threatening trauma/s”; c) substance abuse disorders, developed in order to dampen the strong psychobiological response to trauma and/or losses; and, d) suicide, as a expression of “extreme hopelessness and forsaking” and/or of “intense anxiety overload” that may end in suicidal ideation, suicide attempt or completed suicide.

Not all individuals exposed to the same traumas and losses develop the above mentioned disorders. We have seen that some experiences (such as torture or sexual assault) are more frequently related to disabling sequelae than others.

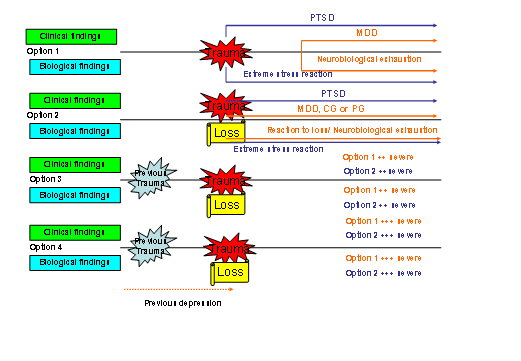

PTSD is said to be the most prevalent lifetime disorder after war exposure, followed by major depression, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and phobic disorder. Unlike generalized anxiety disorder and past substance use, the mean onset of phobias, major depression, and panic disorder, respectively, tends to occur later than PTSD (9). The phenomenological and neurobiological findings concerning the relationship between PTSD and MDD after trauma are simplified and depicted in Fig 1.

Figure 1. Schema of Posttraumatic mood disorder (PTMD)

(PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder; MDD: Major depressive disorder; CG: complicated grief; PG: prolonged grief)

This simplified model can be complicated when adding the effect of previous, current and future psychobiological and socio-cultural conditions of individuals who endure trauma and/or loss during a given war period. Some other clinical categories such as substance abuse disorders may also overlap with comorbid MDD and PTSD complicating the course of the suffering. Moreover, this model could be improved when depicting a new integrative brain-mind theory.

Suicide can be viewed as a process that starts with suicidal ideation and can be followed by attempted or completed suicide. It can also be understood as a personal intent to stop an unbearable suffering. This intense suffering can last minutes, days or even longer, but it exceeds one’s personal capacity to give any other response but suicide. The process of suicide can be immediate (impulsive) or can last longer (i.e. planned attempts).

Bibliography

- Sher L. A model of suicidal behavior in war veterans with posttraumatic mood disorder. Med hypotheses 2009 Aug;73(2):215-9.

- Somasundaram DJ, Sivayokan S. War trauma in a civilian population. Br J Psychiatry 1994 Oct;165(4):524-7.

- Karam EG, Howard DB, Karam AN, Ashkar A, Shaaya M, Melhem N, et al. Major depression and external stressors: the Lebanon Wars. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998;248(5):225-30.

- Engdahl B, Dikel TN, Eberly R, Blank A, Jr. Comorbidity and course of psychiatric disorders in a community sample of former prisoners of war. Am J Psychiatry 1998 Dec;155(12):1740-5.

- Nelson BD, Fernandez WG, Galea S, Sisco S, Dierberg K, Gorgieva GS, et al. War-related psychological sequelae among emergency department patients in the former Republic of Yugoslavia. BMC Med 2004 Jun 1;2:22.

- Marshall GN, Schell TL, Elliott MN, Berthold SM, Chun CA. Mental health of Cambodian refugees 2 decades after resettlement in the United States. JAMA 2005 Aug 3;294(5):571-9.

- Benda BB. Gender differences in predictors of suicidal thoughts and attempts among homeless veterans that abuse substances. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2005 Feb;35(1):106-16.

- Tanielian T, Jaycox LH, et al. Invisible Wounds of War. Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Santa Monica, CA.: RAND Corporation.; 2008.

- Mellman TA, Randolph CA, Brawman-Mintzer O, Flores LP, Milanes FJ. Phenomenology and course of psychiatric disorders associated with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1992 Nov;149(11):1568-74.