Don’t you know I’m angry?: An analysis on the limited research on anger

Amy K. Grochala, B.A., Jess G. Fiedorowicz, M.D., Ph.D.

Anger is a ubiquitous human emotion that arises when a person feels that they have purposefully been wronged or their efforts to obtain some goals have been thwarted. It can be as mild as irritability or as extreme as rage, and can be kept inward or expressed outwardly in behaviors such as violence, aggression, or hostility to others (1). Whether kept inward or expressed outwardly, anger is typically considered a negative emotion. For example, the average score to a 5-point “attitude toward anger” scale was 1.5, where 1 equals strongly disagree and 5 equals strongly agree with statements that express liking the anger experience (2).

Anger occurs more frequently in some people than in others due to circumstance, personality traits, or psychiatric or neuropsychiatric illnesses, such as bipolar disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, Alzheimer‘s disease, or Huntington‘s disease (3,4,5). Excess anger, whether suppressed or expressed, can lead to physical and mental health problems, such as coronary disease, diabetes, and bulimia nervosa. Although anger is a driving force for serious health issues, treatments are limited, with most focused on altering the behavior of the individual experiencing anger issues (1). Another serious outcome of anger is violent crime, and according to the FBI, in 2015, an estimated 1,197,704 violent crimes took place in the U.S., an increase of 3.9 percent from the prior year (6). Therefore, managing excess and inappropriate anger could have positive benefits for the health and well-being of our society.

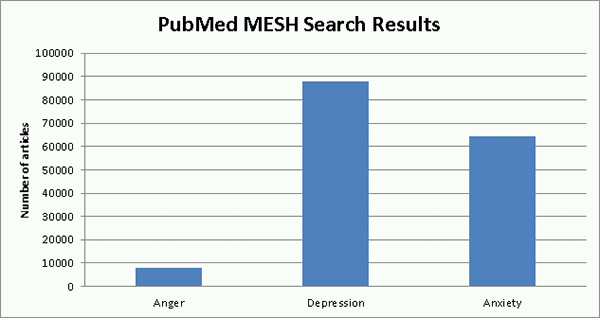

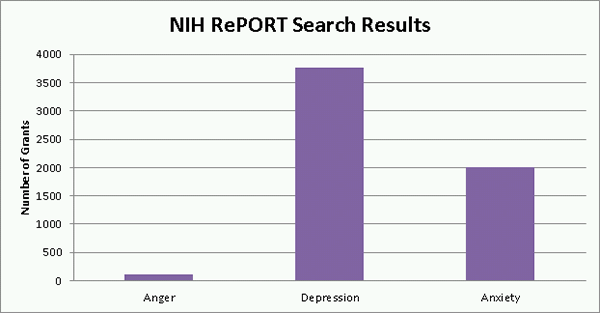

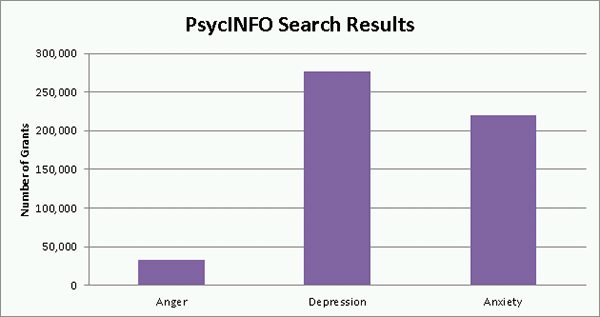

Anger is also arguably an under-studied topic. In a July 20th, 2016 PubMed MESH search on the subject of “anger” and “irritable mood,” those subjects brought up far fewer search terms than the emotions and psychiatric symptoms “depression” and “anxiety”. Searching the MESH phrase “anger OR irritable mood” turns up 8,090 articles. For comparison, for the MESH term “depression” 88,020 articles appeared. Results for “anxiety” were similarly abundant, with 64524 articles. Figure 1 illustrates the PubMed search results. A July 25th, 2016 search using the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT) and limited to publications starting in the year 2015 and ending in the year 2016, resulted in 114 grants related to anger. A similar search for “depression” resulted in 3764 related grants, and one for “anxiety” ended with 2011 results. Figure 2 shows the RePORT search results. An October 19th, 2016 search using PsycINFO generated similar results. A search for “depression” ended with 276,471 results, and one for “anxiety” had 220,340 results, whereas a search for “anger” only gathered 32,457 results. Figure 3 shows the results of the PsycINFO search. Overall, anger appears to be approximately 10 times less likely to be researched than depression or anxiety, even though anger occurs everywhere and has considerable public health impact.

Along with having fewer results than the other search terms, many of the articles that showed up in the MESH search for “anger OR irritable mood” did not focus on either term as the main subject. For example, the paper “Autonomy and autism: who speaks for the adolescent patient?” showed up early in the search on anger, but autonomy is the major discussion topic (7). Anger plays a part in the story, but this paper is not helpful for someone who wants to learn about the subject of anger. For both the searches for “depression” and “anxiety” and the search for “anger,” papers loosely related to the topics showed up in the results, which may affect one‘s ability to find useful information during research. This may have more of an impact for the subject of “anger,” which had fewer search results overall.

With the prevalence of health conditions, mental health conditions, and social issues that are related to anger and the commonness of anger in general, more knowledge on this emotion and its effects would be beneficial, especially when considering the current lack thereof.

References

1. Staicu, ML, Cutov M. Anger and health risk behaviors. Journal of Medicine and Life. 2010;3(4);372-5.

2. Carver, CS, Harmon-Jones, E. Anger is an approach-related affect: Evidence and implications. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(2);183-204.

3. Fernandez, E, Johnson, SL. Anger in psychological disorders: Prevalence, presentation, etiology and prognostic implications. Clinical Psychological Review. 2016;46;124-35.

4. Suarez-Gonzalez, A, Crutch, SJ, et al. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Posterior Cortical Atrophy and Alzheimer Disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2016; 29(2)65-71.

5. Paradiso, S, Turner, BM, et al. Neural bases of dysphoria in early Huntington’s disease. Psychiatry Research. 2008;162(1);73-87.

6. 2015 Crime in the United States. FBI:UCR. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2015/crime-in-the-u.s.-2015/home retrieved October 7, 2016.

7. Benson, R, Pinnaro, C. Autonomy and autism; who speaks for the adolescent patient? AMA Journal of Ethics. 2015; 17(4):305-9.

Figure 1. Articles related to the topics of “anger,” “depression,” or “anxiety.”

Figure 2. Grants related to the topics of “anger,” “depression,” or “anxiety.”

Figure 3. Articles related to the topics of “anger,” “depression,” or “anxiety.”