Walking is a protective factor against depression in elderly veterans

Yulin Chu, D.N.P.

Millions of years ago, walking on two legs became a key attribute to human development, which distinguished humans from other animals. Since then, we have attained many benefits from walking. Is walking also beneficial to human’s mood? Numerous evidences suggest that physical activity (PA)/walking is a protective factor against depression (Robertson, R., Robertson, A., Jepson, & Maxwell, 2012). Physically active people often demonstrate lower rates of depressed mood than people with sedentary lifestyles and less engagement of PA (Middleton & Yaffe, 2009). Depression is the most frequent cause of emotional suffering and significantly decreases quality of life in older adults (Blazer, 2003).Physical inactivity is also a serious and common problem among the elderly adults. To meet the population needs, this evidence-based project (EBP) is proposed to develop and implement a protocol for nurse practitioners (NPs) to manage depression in geriatric-psychiatric (Geri-Psych) patients of a Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital by prescribing regular walking to improve patient outcomes. Because depression in latelife or latelife depression (LLD) is under detected and undertreated (Starkstein, Mizrahi & Power, 2008), it is crucial to analyze clinical and pathological aspects of walking as a protective factor against LLD and manage it efficiently. As a DNP scholarly project, the aim of this EBP is to evaluate the application of this evidence at a micro-clinic to achieve behavior change and promote healthy aging in elderly veterans at a macro-level of excellence while changing the disease-centred care to the person-centred care.

Practice Problem

The population for this EBP is all veterans who can walk, aged 65 years and older, under the care of the psychiatric NPs in the Geri-Psych clinic and group. They are selected according to their schedule availabilities. The population problem is that they are vulnerable to develop LLD and have limited PA. In additions, there is a relatively lower efficacy and higher side effects of antidepressants for this population.

Nearly 7 million Americans aged 65 and older suffer from depression (Kerr, 2012). While the rates of depression are fairly low for the elderly adults living on their own, 1-5%, the rate in elderly veterans (11%) is more than twice that found in the general population (Kerr, 2012). The actual rate of depression among older veterans may be even higher, since not all veterans with depression receive a diagnosis from their health care provider (United States Department of Veterans Affairs [VA], 2011).

The patients in VA clinics are primarily older males who have below average socioeconomic resources and above average medical comorbidity and functional disability (VA, 2014). Hispanic and African American veterans have been rising in population percentages and will continue rise in the future (VA, 2013). These elderly minority are vulnerable to develop depression, behavioral problems, or totally loss of function. In this Geri-Psych clinic, depression is the most common psychiatric illness (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Population (N= 36)

| Characteristics | N | M or % |

| Age, years | 36 of 66 – 90 yo | 82 yo |

| Geri-Psych clinic | 24 | 69% |

| Geri-Psych group | 12 | 34% |

| Black | 13 | 36% |

| Hispanic | 13 | 36% |

| White | 10 | 28% |

| DSM-V diagnosis (Dx) | No. of Dx | Dx % |

| Depressive disorder | 20 | 57% |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 12 | 34% |

| Dementia/MCI | 11 | 31% |

| Anxiety disorder | 9 | 26% |

| Alcohol/drug abuse Hx | 8 | 23% |

| Insomnia | 5 | 14% |

| Bipolar + OCD + psychosis | 4 | 11% |

However, many elderly veterans do not recognize and report their depression problems; up to 90% of people who suffer from LLD don’t receive adequate care (Kerr, 2012). The comorbid depression and cognitive impairment may lead to anxiety, agitation, and behavioral problems, which are more likely to be treated by antipsychotics (Evans, 2011). Wide use of antipsychotics among the elderly not only further impairs their cognition but also significantly increases their mortality (Evans, 2011).

One of the most serious consequences of depression is suicide. Veterans 65+ are at high risk of suicide compared to middle-aged veterans. Other serious consequences include increased risk for medical problems, cognitive decline, and non-suicidal mortality (VA, 2011).

On the other hand, physical inactivity is a common problem among the elderly veterans with depression and multiple medical comorbidities. About 17% of deaths in the U.S. were due to poor diet and physical inactivity, and about 48% of all deaths were due to behavioral contribution (Kinsinger, Pittman, & Shiffler, 2010). About 25 % of the U.S. population reported zero leisure-time PA. PA also tends to decline as people age (Weir, 2011). Narzarko (2010) reported that older people living in a care home spend around 50% of their time asleep or resting and only 5% of their time engaged in constructive activity.

As a conclusion drawn from the above empirical evidence: We should use PA (walking for elderly patients) as a safe, effective, and feasible way to prevent and treat LLD.

PICOT Question

PICOT question: For the elderly veterans (65 years and older) who can walk, does a protocol of prescribing regular walking in 2 months reduce the symptoms of depression and functional impairment by comparing their pre-and post-intervened test scores? The research assumption is: The patients would have reduced scores on depression and functional impairment than their pre-test scores. This assumption is based on previous evidence, facts, and empirical data of the studies (Williams & Kemper, 2010), as well as the national clinical guidelines.

Population problem. The Electronic Medical record (EMR) of all veterans who can walk, aged 65 years and older, under the care of the psychiatric NPs in the Geri-Psych clinic and group of the VA hospital are all selected according to their schedule availabilities during the two months of the study. The problem is that these patients are vulnerable to develop LLD and have limited PA while there is relatively lower efficacy and higher side effects of antidepressants for them.

Intervention. The main intervention will be the implementation of a protocol to prescribe regular walking to the patients who can walk after the NPs carefully assessed them. “Walking Questionnaire&lrquo; (Table 2) is designed by the NPs to assess patient’s history and physical capability of walking based on their self-report.

Table 2. Walking Questionnaires

Please, all answer the first question:

- Are you physically able to walk with or without a device (not includes a wheelchair)?

Yes or No.

If you answered “Yes,” go to the next question; if you answered “No,” escape the following questions and submit it now.

For the people who can walk, please answer the following questions:

- How long can you walk at one time without physical difficulty?

- 10 minutes

- 20 minutes

- 30 minutes

- more than 1 hour

- How many times you normally walked daily?

- 1 time

- 2 times

- 3 times

- 4 times or more

- How often do you go for a walk?

- 1 day/weekly

- 2 days/weekly

- 3 days/weekly

- more than 4 days/weekly

Education regarding the benefits of walking to improve physical, mental, and cognitive status is provided during the routine clinics prior to start walking. Individuals who do not meet optimal goals of walking should get at least an additional 10 minutes of walking above what they are already doing daily to reach Minimal Goal. Healthier Goal is prescribed to the people who can walk with mild- to moderate-intensity of PA: A minimum of 30 minutes daily and 5 days/week of walking as recommended by National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) (Kottke et al., 2013). A pedometer is given to each patient who is willing and able to walk, and visited the clinic and group during the study time as an objective measurement and a subjective stimulator to their walking.

Comparison. It is designed to compare all patients’ pre-and-post-intervened scores of the standard tests and measure the results of the mood and functional changes after the completion of the protocol implementation. The measurement tools include Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ). The GDS and FAQ are the standardized tools we have been using in routine psychiatric practice recommended by NGC (NGC, n.d.) and National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) (Mayo, 2012) to assess depression and function in geriatric population. FAQ includes ADLs, social and independent living skills, and cognitive function. Because the validity and reliability of GDS and FAQ are high, and their questionnaires cover all major areas of mood and function, some elderly veterans denied or did not recognize their depression and functional impairment but are detected by the tests, and therefore they can get the necessary treatment at early stages.

The data collection method is chart review.

Outcomes. The positive outcome is estimated that there is a reduction from pre-intervened to post- intervened depression and decreased functional impairment among the patients who compliant with their prescribed walking and reached either Healthier or Minimal Goal. After the data analysis, the results of this EBP showed positive: There is a significant reduction of GDS and FAQ scores from pre-to-post-tests, which meet the above goal of this project. Comparing to GDS, FAQ score change is estimated to be slower due to relatively long term pattern of its progressive changes among.

Timeline is about two months for intervention.

Synthesis of the Literature

Rationales for the project. Literature explored that LLD has its own special features comparing to depression in general populations. It is highly connected with multiple physical chronic illnesses and cognitive impairment. The prevalence of depression in Alzheimer’s disease is up to 50% (Lyketsos & Olin, 2002). The detection and efficacy of pharmacological treatment of LLD is limited due to lack of insight of depression, unrecognized and unreported symptoms, and overlap with apathy, anxiety, agitation, or aggression of Alzheimer’s disease (Lyketsos, 2012). The treatment challenge of LLD is side effects from antidepressants and nonadherence of medicine. One study showed that up to 2/3 of older veterans discontinue antidepressants (VA, 2011). This evidence raised the motivation of this project to search for a safer, more effective, and a feasible way to prevent and treat LLD.

Effect of walking on depressed mood

Numerous evidences support that PA improves old adults’ physical health and depressed mood, and promotes quality of life (Drewnowski & Evans, 2001). Harris, Cronkite, and Moos (2006) conducted a large quantitative 10-year cohort study and found that more PA is associated with less concurrent depression; PA also counteracts with the effects of medical conditions and negative life stressors on depression.

Bridle et al. (2012) has done the first Meta-Analysis of only Randomly Controlled Trials to estimate the effect of exercise on depression severity among older people with severe depression. Their findings are consistent with the suggestion that prescribing structured exercise tailored to individual ability will reduce depression severity. Robertson et al. (2012) further focused on walking by conducting a Meta-Analysis of Randomly Controlled Trials, and revealed that walking has a significant effect on depression in some populations.

Strohle (2009) summarized the research findings: 1. PA is associated with a range of health benefits, and its absence can increase the risk of CAD, DM, certain cancers, obesity, HTN, mortality, and develop some mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety. 2. PA stimulates a complex system and trigger a cascade of events, which result in higher resilience against mental disorders, including depression. 3. Moderate intensity activities such as walking are more successful than vigorous physical activity; daily at least 30 minutes of walking is encouraged.

Practice recommendations

Based on the evidence, the NPs proposed: 1. Walking is associated with less concurrent depression. It is a safer, more effective, and a feasible way to prevent/treat LLD. 2. By two months’ monitoring of patients walking and assessing patients, there may be the improved mood and overall function. The positive result may be contributed to regenerate this evidence-based practice. 3. We should add prescribing of regular walking into the LLD treatment plan, and change the disease-centred care to person-centred care.

Project Setting

It is a Geri-Psych outpatient clinic in a VA hospital with above 700 patients. It is a secondary level of care provided by psychiatric specialists and professionals who treat/maintain the treatment of mental disorders. The veterans are primarily old males with increased Hispanic and Africa American populations who have below average socioeconomic resources and above average medical co-morbidities and functional disabilities (VA, 2014) (Table 1). All staffs in clinic support this EBP and are interested in searching the effect of walking on depression and patient function.

Human Rights Protection and Patient Safety

The project applied and is approved by both IRBs prior to its starting. Throughout the entire project implementation and evaluation, the chart review without any human subject involvement is the only method for data collection. All depression and functional assessments are done individually during the routine clinics. All available charts are selected to avoid selection bias. HIPPA privacy policy and IRB regulations are followed throughout the project process. There is no any individual information exposed.

To improve patient safety and respect the elderly veterans’ specialty and vulnerability, NPs did not prescribe walking to the patients who cannot physically ambulate. People who have already enrolled the walking program but suffer from physical condition change or the stress caused by negative life event are allowed to withdraw from the program to protect safety. The NPs also ensured that the demented patients always walk with companies. In summer days, the NPs educated patients to walk in early morning or evenings to avoid heat. During the period of study, there is no any report of falls or incidents related to walking.

Project Evaluation

Data types. The independent variable (IV) is walking. The dependent variables (DVs) are the post-intervened depressive symptoms measured by GDS, and the changed functional impairment on FAQ.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. The EMRs of the patients 65 +, who can physically walk at least 10 minutes continually are included; the EMRs of the veterans who are under 65 years old and who cannot walk are excluded. There are 38 patients who meet the criteria, and 36 of them completed the program with either Healthier or Minimal Goal (compliance rate = 95%). There is no gender confounder (all participants are male). Because the study is designed to measure the impacts of walking on depression, the statistical analysis is based on the depressed patients only. The cut-off score of diagnosing depression is <3 (depressed patients, N=25).

Data analysis. The main statistical method is a paired 2-tailed t-test (walking may affect mood in either direction) within subject design since this study compares the two samples that are the same population. The results from both Data Analysis Toolpak (DAT) and SPSS are same, and it is displayed in Table 3. The primary outcome of this study is the significantly reduced symptoms of depression (GDS score change: t (24) = 5.317, p < 0.001) and decreased functional impairment (FAQ score change: t (24) = 3.468, p < 0.001). Descriptive statistics are used to describe the numbers of the participants and possible covariates (Table 1).

Table 3. t-test in SPSS

Paired Samples t-Test for GDS

| Pair 1 | Paired Differences | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) |

||||

| Mean | Std. Deviation |

Std. Error Mean |

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

|||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Pre-test -Post-test |

2.720 | 2.558 | .512 | 1.664 | 3.776 | 5.317 | 24 | .00002 |

Paired Samples t-Test for FAQ

| Pair 1 | Paired Differences | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) |

||||

| Mean | Std. Deviation |

Std. Error Mean |

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

|||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Pre-test -Post-test |

.880 | 1.269 | .254 | .356 | 1.404 | 3.468 | 24 | .002 |

Interpretation:

From SPSS results, we can see the t-value = 5.317 for test of GDS and 3.468 for t-test of FAQ. From the statistic t Table, the t-critical value = 2.064 for both tests. Because the t-statistic (5.317 and 3.468) is > the critical value (2.064), there is a statistically significant difference between the means of the two groups (yellow highlights). Because the p-value (.00002 for GDS and 0.002 for FAQ) is < 0.01, then the difference between the means has a less than 1% probability of being due to chance (green highlights).

Power analysis. To determinate if this sample (N=25) is large enough that ß is at a reasonable level (80% or more), a post hoc power analysis was conducted using SPSS. The results of power analyses in SPSS shows the power of the GDS t-test = 0.96 and the power of the FAQ t-test = 0.88. Statistically, these results are sufficient for a paired t-test to achieve > 80% power at two-sided 1% significance level. It means the sample size (N = 25) is marginally safe in assuming the dependent variables followed a normal distribution.

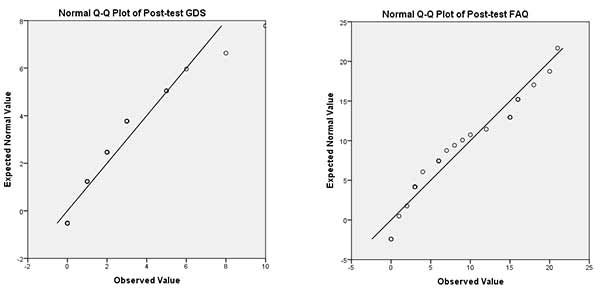

Central tendency of the data. The central tendency is a central for a probability distribution. A normal probability distribution is a prerequisite for a paired t-test to secure the accuracy of the result. In this study, a Q-Q slot used by SPSS shows that the points of each Q-Q plot lie around to its central value, we conclude that each of the data groups is from an approximately normally distributed population (Figure 1).

Study results

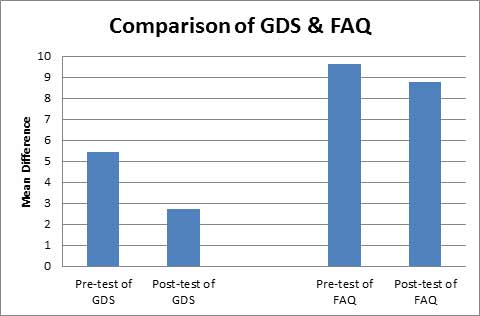

A paired t-test was conducted to compare DVs in relation to IVs (walking). These results [t (24) = 5.317, p < 0.001 and t (24) = 3.468, p < 0.001] suggest that there is a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of pre-and post-tests (Table 3). Since our Paired Samples Statistics box revealed that the mean numbers of GDS and FAQ scores of pre-walked patients were greater than the means of the post-walked patients (Figure 2), we can conclude that participants in walking were significantly reduced their scores of depression and functional impairment than their scores in pre-walked condition. Besides the above statistical results, the narrative reports from the participants typically are: the enjoyment of walking, happier mood, increased motivation for activity, more productivity, and more socialization in post-walking.

Discussion

Strengths of the study: 1). The study uses all of the patients who meet the inclusion criteria and are available in clinical schedules (population) as the sampling, and there is a limited selection bias. 2). The study uses standard tools recommended by NGC and NACC – GDS and FAQ, which have high validity and reliability, and we have been using them in daily psychiatric practice. The tools used are contributed to the accuracy, validity, and reliability of the results. 3). This DNP scholarly project is conducted based on the evidence, and it found the positive result of walking to improving depression and function in Geri-Psych patients. 4). The project uses developing and implementing a protocol method, which is integrated with the scope of practice for nursing and presents the best practice for quality improvement. 5). We have strong milieu and background for this project in VA. All of the patients under the NPs’ care are willing to walk. All staff in Geri-Psych clinic is served as the human resources for support. This study is a low-cost study – only 50 pedometers and paper-pencil tests as the materials needed for the study.

Weaknesses. 1). The study does not have a control group (the depressed but not walked patients) comparing with the case group (the depressed and walked patients) for the outcomes. 2). The NPs do not have the experience to do this kind of project in the past; there is no current result of similar nursing research in VA healthcare settings; the time frame for the project (2 months) is relatively shorter.

Implications. This EBP is to apply and reevaluate the evidence in micro-clinic (a small size of Geri-Psych clinic in this VAH) to achieve behavior change and promote healthy aging in macro-level excellence (perhaps in other clinics of this hospital or other VAHs), and to change the disease-centred care to person-centred care. The implication of the study is: 1). Walking can increase the treatment outcomes of the depressed elderly veterans. This EBP applied and reevaluated the evidence of walking as a protective factor against LLD. 2). The positive results provide the support evidence in generalizing similar studies or practice. 3). It supports the EBP as a good training method and model for DNP educational program.

Conclusion

As a DNP scholarly project, the aim of this EBP is to evaluate the application of the evidence of walking on improved patient depression and function in micro-clinic in order to achieving behavior change and promoting healthy aging of elderly veterans in macro-level of excellence, and to changing the disease-centred care to person-centred care. Through the protocol’s development, implementation, and evaluation, this EBP is completed with the positive outcomes. By designing and conducting the EBP, the DNP student not only evaluates the study positive outcomes in micro level, but also contributes the relevant evidence in VA meso-and-macro clinical practice to replicate the intervention. In addition, the DNP student demonstrates the advanced level of the conceptual ability and analytical skills for policy/protocol development, and achieved practice and scientific requirements for a DNP.

References

Blazer, D. G. (2003). Depression in late life: Review and commentary. Journal of Gerontology: MEDICAL SCIENCES, 58A (3), 249- 265.

Bridle, C., Spanjers, K., Patel, S., Atherton, N. M., & Lamb, S. E. (2012). Effect of exercise on depression severity in older people: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and controlled trials. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 201, 180-185. doi: 10.1992/bjp.bp.111.095174

Drewnowski, A. & Evans, W. J. (2001). Nutrition, physical activity, and quality of life in older adults: Summary. Journals of Gerontology, 56A, 89-94.

Evans, J. (5/1/2011). Caring for the ages. AMDA. Retrieved from http://www.caringfortheages.com/issues/may-2011/single-vview/the-ethics-of-antipsychotics-in-alzheimer/ba6ff721b07f61a5d15888345dd9e1bc.html

Harris, A., Cronkite, R., & Moos, R. (2006). Physical activity, exercise coping, and depression in a 10 year cohort study of depressed patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 93 (1-3). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.013

Kinsinger, L., Pittman, K., & Shiffler, J. (2010). Chief consultant for preventive medicine: Healthy living messages for veterans VHA’s federal partners in prevention. Health POWER! Retrieved from http://www.prevention.va.gov/healthpower/HealthPower2010WinterlFinal.pdf

Kottke, T., Baechler, C., Canterbury, M., Danner, C., Erickson, K., Hayes, R., Marshall, M., O’Connor, P., Sanford, M., Schloenleber, M., Shimotsu, S., Straub, R., Wilkinson, J., & Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Updated ed. (2013). Healthy lifestyles. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Retrieved from https://www.icsi.org/_asset/4qjdnr/HealthyLifestyles.pdf

Lyketsos, C. G. & Olin, J. (2002). Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: Overview and treatment. Sociaty of Biological Psychiatry, 52, 243-252. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12035/pdf

Lyketsos, C. G. (2012). Treating Depression in Alzheimer’s Patients. Memory Disorders Review, Summer Issue; page: 22-32.

Mayo, A. M. (2012). Use of functional activities questionnaire in older adults with dementia. Try this, Issue: D13. Retrieved from http://consultgerirn.org/uploads/File/trythis/try_this_d13.pdf

Middleton, L., & Yaffe, K. (2009). Promising strategies for the prevention of dementia. Archives of Neurology, 66(10): 1210-1215. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2009.201

Narzarko, L. (2010). Creative care: How an active life can benefit physical and mental health. Nursing & Residential Care, 12(7), 314-316.

National Guideline Clearinghouse. (n.d.). Depression in older adults. In: Evidence-based geriatric nursing protocols for best practice. Retrieved from http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?f=rss&id=43922&osrc=12

Robertson, R., Robertson, A., Jepson, R., & Maxwell, M. (2012). Walking for depression or depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 5, 66-75. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2012.03.002

Span, P. (2013). Suicide rates are high among the elderly. New York Times, 8/7/2013. Retrieved from http://newoldage.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/08/07/high-suicide-rates-among-the-elderly/?_r=0

Starkstein, S. E., Mizrahi, R., & Power, B. D. (2008). Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: Phenomenology, clinical correlates and treatment. International Review of Psychiatry, 20(4), 382-388.

Strohle, A. (2009). Physical activity, exercise, depression and anxiety disorders. Journal of Neural Transmission, 116, 777–784. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0092-x.

United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2011). One in ten veterans is depressed. Retrieved from http://www.va.gov/health/NewsFeatures/20110624a.asp

United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2013). National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease: 2013 update [Adobe Digital Editions version]. Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltop/napa/NatlPlan2013.pdf

Weir, K. (2011). The exercise effect. Monitor on Psychology, 42 (11), 48.

Williams, K. N. & Kemper, S. (2010). Interventions to reduce cognitive decline in aging. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 48 (5), 42-51. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20100331-03