The underrepresentation of tornado disasters in post-traumatic stress disorder literature

Scott A. Laurenzo, Jess G Fiedorowicz, M.D., Ph.D.

Disasters, wars, and other devastating events have the potential to cause post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This diversity of events and settings may influence study of the disease’s course. With regard to natural disasters, current research over-emphasizes the short-term effects of single events covering large areas such as hurricanes. Meanwhile, communities affected by other disasters such as tornados are underrepresented in the PTSD literature. Considering years as recent as 2004 and 2011 are some of the most active years for tornados in the United States, one might expect a large post-tornado PTSD research literature (1).In the average year, there are over 1,000 tornados reported in the United States, which create many opportunities to study the effects of tornados on PTSD (2). However, large databases such as PubMed and PsychInfo, as well as many journals, disproportionately focus on PTSD after less frequent natural disasters such as hurricanes, which usually make landfall in the United States twice a year (3). It is important to study a more broad representation of disasters because the unique exposures and characteristics of natural disasters influence the development and prognosis of mental illness in the effected population.

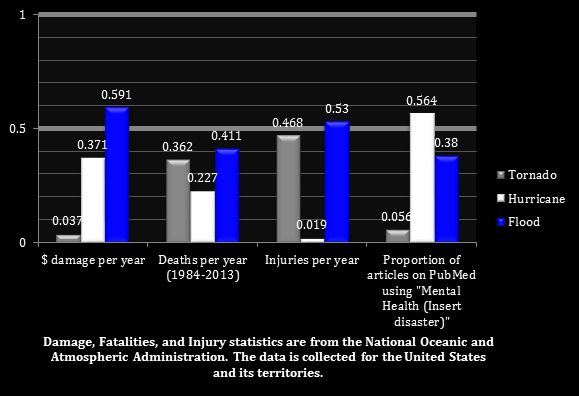

Tornados can form in any location throughout the world although the United States reports the most tornados annually (4). These storms cause an average of 75 fatalities, 1500 injuries, and $500 million in damages each year (2, 5, 6). Besides tornados, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) also provides detailed data for hurricanes and floods occurring in the United States. The administration’s consistent and reliable recording methods make the comparisons of tornados, hurricanes, and floods reliable across these specific disasters. Information for other types of disasters in the U.S. and other countries can be found from other sources, but would introduce variability in data collection and recording methods. The NOAA reports that hurricanes in the U.S. cause an average of $5 billion in damages each year and are associated with 47 fatalities in the average year (2, 6, 7). Although hurricanes cause ten times the monetary damage compared to tornados, the number of fatalities and injuries are usually much less. This difference is associated with the relatively lengthy advanced warnings typically available for hurricane landfall, compared to the minutes-long advanced warnings available for tornados. U.S. floods cause an average of $7.96 billion in damages each year and an average of 82 fatalities each year (6-8). Figure 1 visually compares the proportions of monetary damage, injuries, and fatalities caused by each of these three disasters. The fourth column also compares the proportion of articles displayed following a PubMed search of “Mental Health (Hurricane, Tornado, or Flood).” Being injured, socioeconomic damage, and being close to a person who died due to a natural disaster are known risk factors for developing PTSD post-disaster (9-11). This might suggest that the proportion of articles for each disaster would be positively correlated with the proportion of monetary damage, injuries, or deaths. However, it is evident by Figure 1 that this is not the case, and that there might be an unjustified bias in the available literature.

Although natural disasters as a whole have been associated with a high incidence of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse, the psychological effects of different types of disasters is variable (12). The large range (5%-60%) of PTSD incidence following disaster is assumed to be due to the variety of exposures, severity, and nature of different disasters (13). Research focusing on the little analyzed, tornado disaster event could detail key differences.

Another reason to study mental health in the context of tornado disasters is the inequality between people affected by tornados. As it was mentioned previously, being injured or being close to someone who died due to disaster are risk factors for developing PTSD (9). Taking shelter in a mobile home during a tornado disaster is associated with an increased odds for injury compared to a permanent home (14). Since mobile (manufactured) homes are more affordable than permanent homes, persons with lower socioeconomic status might be more likely to develop PTSD compared to higher socioeconomic statuses. This relationship is also important to consider because socioeconomic status is an important determinant for mental illness susceptibility, and also helps determine the ability to withstand a financial loss following disaster. Both are factors that can increase a person’s susceptibility to PTSD following a tornado (10, 15). More specific studies could examine these associations and inform further research into fostering resilience or safe behaviors among these populations.

Following disasters, there is an emphasis placed on short-term care for mental health, but PTSD can require treatment for years after a disaster. PTSD-like symptoms developing within 4 weeks of the disaster can be considered an acute stress disorder that usually does not require further treatment. This emphasizes the misconception that only short-term care for post-trauma mental disorders is necessary. If the symptoms resolve within three months, PTSD is considered acute, but resolution taking longer than three months is considered chronic. Approximately 60% of PTSD cases will resolve themselves acutely, but many will continue into the chronic stage with the average duration of symptoms lasting 64 months untreated, but only 36 months if the individual was treated (16, 17). Due to the chronic nature of PTSD, longitudinal research following PTSD patients for years rather than just a few months might help to decrease the recovery time or the number of patients developing chronic PTSD.

Since PTSD is shown to have long-term effects on individuals, which can vary based on the nature of the trauma, it is important to increase the amount of longitudinal research for the underrepresented natural disasters. This requires more than simply reexamining the incidence of PTSD following a disaster. For example, increasing the amount of available literature for tornado PTSD is needed to create programs that could educate community leaders, or parents on methods for increasing resilience in their dependents. One study found a connection between parental PTSD symptoms and their children’s PTSD symptoms (19). Further research that elucidates the details of this connection may help to create a methodology for preventing PTSD following future disasters. A new emphasis should be placed on longitudinal studies that examine the development, treatment, and resolution of PTSD following the frequent tornado disasters as well as other underrepresented disasters occurring each year.

References

1. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. 2011 Tornado Information: United States Department of Commerce; 2012. Available from: http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/2011_tornado_information.html.

2. Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Hurricanes and Tornadoes: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; 2012 [cited 2015 June 1]. Available from: http://www.prh.noaa.gov/cphc/pages/FAQ/Hurricanes_vs_tornadoes.php.

3. Blake E, Rappaport E, Jarrell J, Landsea C. The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2004 (And Other Frequently Requested Hurricane Facts). Miami, FL: National Hurricane Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2005.

4. National Centers for Environmental Information. US Tornado Climatology: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; 2011 [cited 2015 June 5th]. Available from: http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/climate-information/extreme-events/us-tornado-climatology.

5. U.S. Department of Commerce. Thunderstorms, Tornadoes, Lightning…Nature’s Most Violent Storms. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

6. McNeill A. Annual Disaster/Death Statistics for US Storms. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Wind Science and Engineering Research Center.

7. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Natural Hazard Statistics: Office of Climate, Weather, Water, and Weather Sercices.; 2014 [cited 2015 June 1]. Available from: http://www.nws.noaa.gov/om/hazstats.shtml.

8. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Hydrologic Information Center-Flood Loss Data: National Weather Service; 2014 [cited 2015 July 8]. Available from: http://www.nws.noaa.gov/hic/.

9. Neria Y, Nandi A, Galea S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2008 Apr;38(4):467-80. PubMed PMID: 17803838. eng.

10. McMillen JC, Smith EM, Fisher RH. Perceived benefit and mental health after three types of disaster. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997 Oct;65(5):733-9. PubMed PMID: 9337492. eng.

11. Secretariat (for the development of a comprehensive mental health action plan). Risks to Mental Health: An Overview of Vulnerabilities and Risk Factors 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/risks_to_mental_health_EN_27_08_12.pdf.

12. North CS. Current research and recent breakthroughs on the mental health effects of disasters. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014 Oct;16(10):481. PubMed PMID: 25138235. eng.

13. Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiol Rev. 2005;27:78-91. PubMed PMID: 15958429. eng.

14. Niederkrotenthaler T, Parker EM, Ovalle F, Noe RS, Noe RE, Bell J, et al. Injuries and post-traumatic stress following historic tornados: Alabama, April 2011. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83038. PubMed PMID: 24367581. PMCID: PMC3867464. eng.

15. Secretariat (for the development of a comprehensive mental health action plan). Risks to Mental Health: An Overview of Vulnerabilities and Risk Factors. 2012.

16. Foa EB, Stein DJ, McFarlane AC. Symptomatology and psychopathology of mental health problems after disaster. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67 Suppl 2:15-25. PubMed PMID: 16602811. eng.

17. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995 Dec;52(12):1048-60. PubMed PMID: 7492257. eng.

18. Polusny MA, Ries BJ, Schultz JR, Calhoun P, Clemensen L, Johnsen IR. PTSD symptom clusters associated with physical health and health care utilization in rural primary care patients exposed to natural disaster. J Trauma Stress. 2008 Feb;21(1):75-82. PubMed PMID: 18302175. eng.

19. Polusny MA, Ries BJ, Meis LA, DeGarmo D, McCormick-Deaton CM, Thuras P, et al. Effects of parents’ experiential avoidance and PTSD on adolescent disaster-related posttraumatic stress symptomatology. J Fam Psychol. 2011 Apr;25(2):220-9. PubMed PMID: 21480702. eng.

Figure 1: Comparison of Tornado, Hurricane, and Flood Literature Availability (with Other Relevant Hazard Values) (2, 5-7) Note: The fourth column “Proportion of Articles on PubMed” is based on the number of results that are shown during a PubMed search for “Mental Health (tornado, hurricane, or flood).”